Sue Langstaff did her PhD on evaluation of the mouthfeel of beer under Michael Lewis who happens to be in charge of the program here at Davis. She has a company called Applied Sensory that does tasting and consulting for the wine, beer, and olive oil industries here in California and worldwide. I'm quickly realizing the benefit of being introduced to the wealth of knowledge here in Davis. It seems like every time I turn around there is someone like Sue who is an expert in something I am looking to learn about.

So every Friday after lunch Sue lectures for about 1.5 hours about sensory science. Last week it was all about how the sensory system works physiologically (smell being tied to memory, neuroscience, different types of chemo-receptors, etc.) and we developed a baseline for the different big taste groups you tend to encounter with beers.

This is a kind of fun experiment you can do at home. If you can't read the picture, the tastes are sweet, sour, bitter, and astringent. And to make them you use table sugar, citric acid, caffeine, and alum. You can find this stuff at grocery stores (I'm not certain about the alum but I know it is in stiptic pencils). If you're not feeling ambitious enough to do your own experiment, here is how I describe these flavors:

Sweet: Sugar, honey...this is the easiest one. Smooth and makes you salivate a lot.

Sour: Lemon...lime has more flavor and orange is sour/sweet which is a bit misleading. Puckering but pleasant. Acidic.

Bitter: Like when you suck on a Tylenol (not the chew-able kind). Bitter is probably the toughest of these four to distinguish as it is easily confused with sour and astringent. Kind of like bile.

Astringent: Like when you bite into a banana peel that is not yet ripe. Drying of the mouth, raspy friction feeling.

After we tasted the baseline solutions, we did a blind test of four beers that each individually represented each of these characteristics to give us a context for how these main tastes fit into the beers we drink. Tasting beers after reference solutions gives you a new appreciation for how complex beer is.

Today Sue's lecture was an introduction into evaluation of beer. We talked about how to train people to report on a similar basis what they taste in a beer. This deals a lot with statistics and psychology and isn't as interesting as what we did later in the afternoon. This afternoon was probably one of the top 3 things I was looking forward to at Davis. And here is what we did...

Sue brought in these reference standards which are pure versions of the chemicals that cause certain distinctive flavors in beer. Some are desirable flavors: Hop Oil. Some are undesirable flavors: Hydrogen Sulfide (rotten eggs). And some are desirable or undesirable depending on who you ask: Lightstruck (skunky, think Heineken or Rolling Rock). There are 20 reference standards, each representing a unique scent/flavor.

I took notes while we were smelling. I wrote the name of the standard and then gave my description of the scent. It is important for us to be able to link a smell to a verbal description so we can continually come back to that description and compare and communicate with other tasters. Your olfactory bulb is part of the limbic system which is strongly tied to memory. It also feeds directly into the amygdala which is the part of your brain responsible for emotion. So unlike your other senses that are processed in other parts of your brain, smell is being processed in such a way that recalls memories and creates emotions. This provides you with a strong feeling about a smell, but when you try to verbalize that feeling often you find yourself at a loss. If you look at my notes above, I could smell all 20 of the reference standards which is good. For 10 of them (starred to the left), I had a strong opinion regarding what they smell like and can relate it to something known. For example, caprylic acid smells like goat cheese to me. It is earthy and sort of sticks in the back of your throat. So since I have a strong feeling about how goat cheese smells, when I try a beer if it smells like goat cheese I know that caprylic acid is likely present.

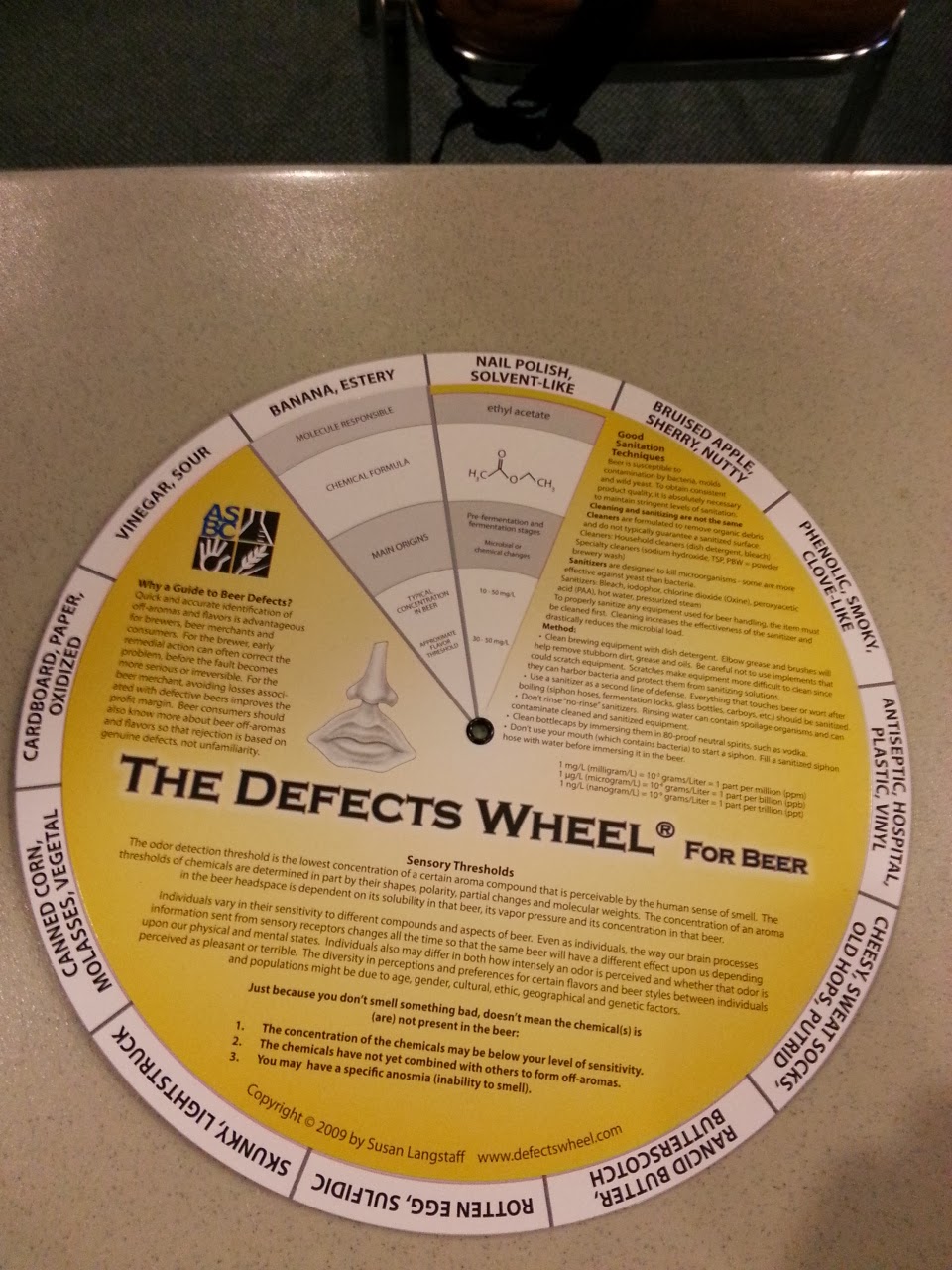

Sue gave us this sweet sensory wheel to help us when we're learning about these things. Around the outside is the type of aroma such as "Nail polish, solvent-like." So when you try a beer and you recognize a scent, you turn the wheel to that scent and you learn about the molecule(s) responsible for it and the likely flaws in your process that caused it.

Beer is interesting that way. Quantifying the quality of our beer is not as simple as running it thorough a GCMS or performing HPLC (for you doctor or biochem nerds out there). There are hundreds if not thousands of chemical compounds in a single beer and high-tech means only get you so far. It is not just the magnitude or number of peaks you see on your GCMS output that matters. The interaction of all of those flavor compounds in concert is what makes a beer unpleasant or unforgetable. In the end, beer quality can only ever truly be determined by tasting. So keep practicing!

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment